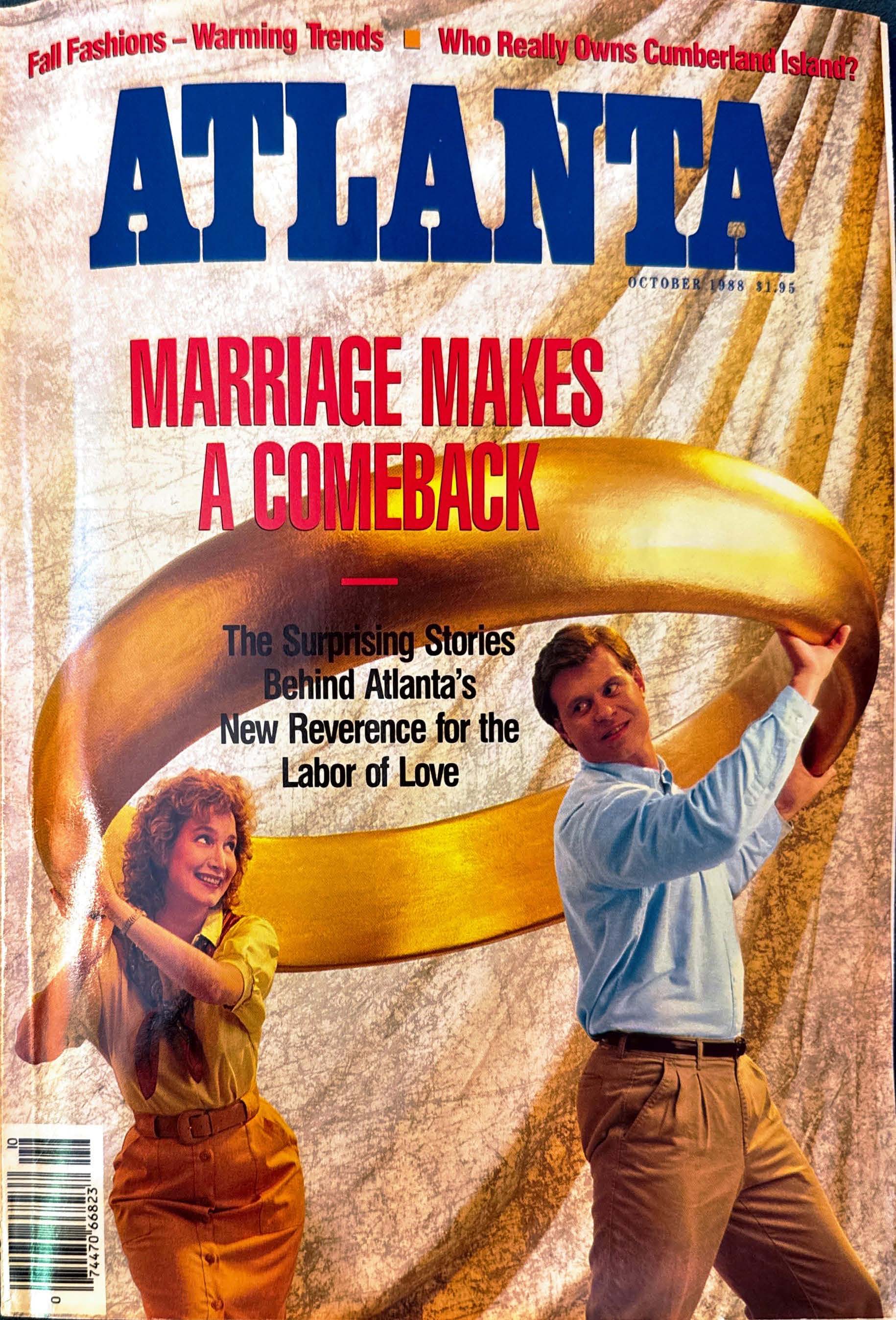

Second Time Around

Originally published in

Atlanta Magazine

Oct 1988

I have a strange mixture of affection and contempt for the 21-year-old me who, five days out of college, married her best friend’s boyfriend’s roommate in a flower-and-candle-filled church because it was so obviously the right thing to do.

But I don’t quite know what to make of the 32-year-old me who married, in somebody’s back yard in California, an alcoholic writer with three children and no money, largely against her — my — better judgment because I wanted to.

Throughout most of my first marriage, divorce was unthinkable. It simply never occurred to me to see it as a possibility or certainly not as a solution to unhappiness. Even after it became obvious that divorce was the only solution, I couldn’t be the one to suggest it. I had to wait until my then-husband said, “Maybe we ought to get a divorce,” and then say, “I wish I’d thought of that.”

But it didn’t take long to determine that if I survived one divorce, I could survive another.

So throughout much of this second marriage, I kept the notion of divorce as a secret plan of escape, a poison pill I carried around, a way out. I could always leave. I came to prize the option, even though I was never sure I could bring myself to exercise it. But I made sure he knew everything was at stake—money, IRS returns, his alcoholism. I was prepared to leave at any time.

I would actually much rather tell you about the first marriage than the second one. No. 1 is dead and buried, safely in the past. It has, in many respects, the reality of a short story I might have read a long time ago. (Do I really know the woman who stood in the middle of a kitchen in Tallahassee, crying into dirty dishes and kitchen items, trying to decide whether to take the good frying pan and leave him with the one with the loose handle? The woman who paced and unpacked three times before concluding that she would rather be fed because she’d be a chump one last time than because she had taken a final cheap shot?)

Marriage No. 2 is alive and therefore vulnerable and fragile in the manner of all living things. (And besides, bad marriages produce snappy dialogue, and good ones produce Hallmark greeting-card verses.)

But here goes: I like the man I am married to. I like his kindness, which is always offered without strings. I like his enthusiasm and his willingness to take risks. I especially liked his “absolutely yes” the first time I broached the idea of a baby. I’ve never had to hold a mirror up to his mouth to see if he was breathing.

I like having common interests, common friends, common jokes. I like the fact that our work is similar enough that we understand and appreciate what the other is doing but not so similar that we compete. Even in the worst times—when his drinking was as awful to us both as it was to him—we shared our work, read it to each other, leveled with each other about it.

But of course the alcoholism became a bigger and bigger reality in the marriage and threatened to override what was good. The arguments got uglier, and the tensions constant. Finally, at crucial points, each of us took an important step.

For my part, I let go of my option—played my trump card—and told him that he could not both continue to drink and continue to be married to me. For his part, he figured out what he needed to do: stop drinking and begin to do it.

It’s very tempting to say that there was a direct cause and effect between what I did and what he did, that he stopped drinking because I forced him to. He actually says so; but I’m less sure.

It was important for me to give up the option, stop hedging my bet, make a commitment. It was important for him to make his own commitment to staying alive. And it’s fortunate that the two separate commitments also worked together.

I found that I could make the decision to get out of the marriage, rather than simply wallowing in the possibility of getting out, and he found that he could stop drinking. Then we found that we wanted to remain in the marriage—I without my escape hatch and he without his vodka.

I’m making this sound much too neat, too reasoned. I didn’t figure it out, then go do it; I did it, then tried to make some sense out of it, as he did.

The tangible sign of all this was moving into a new house—giving up the small place that I felt comfortable with because I knew I could afford it by myself, in case… We even began filing joint tax returns.

I gained closet space and simplified record-keeping along with a nice sense of permanence. I did, somewhere in there, lose some leverage, and I feel that loss occasionally. The balance of power shifted when I gave up my crutch. There’s no denying that things changed—as they needed to.

We still argue occasionally, but our arguments are different, too. Less dramatic, less frustrating. We write and comment about a magazine writing assignment he accepted. I thought he should write it down and told him so. “You ought to be working on your novel,” I said. He said, wearily, “That magazine piece turned out pretty well. The check will come in handy.”

A few days later we were riding in his car, on our way out of town, when he said in a very level, testing-the-waters-of-cool voice, “That magazine piece turned out pretty well.”

“Yeah,” I said, “I told you all along you’d be crazy not to do it. I don’t know why you were such a jerk.”

And we both laughed—which is something I do a lot more of in my second marriage than I ever did in my first.

Click to view the original scans.

Back to Top